1. Introduction

The EU Directive 2019/790 is the most important instrument of reform concerning copyright and derived rights in the area of the Digital Single Market, this directive provides the greatest modification in such field since the adoption of the 2001/29 EC Directive.

Its elaboration has achieved particular notoriety in relation to the articles that regulate the use of copyrighted content concerning what the Directive calls the “online content-sharing service providers” - in short we are referring to the platforms that make possible the diffusion of contents created by their users (such as Facebook and YouTube) - issue now considered by the article 2.6 and above all, article 17.

The discussion on the Directive 2019/790 has been revolving around its specific rules on platforms regarding the diffusion and circulation of user-generated content. The debate within the European institutions (and outside of them) has resulted finally in the exhaustive Article 17. Furthermore, the Directive sets out the reasons for such a provision in its recitals no. 61 to 71. This is a provision that addresses a key issue in the regulation of the Internet and some of its most relevant operators, which justifies the social significance of the debate. This new standard implies a change compared to the past situation since most cases regarding copyrights were still resolved by judges who based their decisions on the 2000/31 Directive.

2. Past and Present

In the framework prior to the reform it was already widely accepted that said platforms are, with respect to the content uploaded by their users, data hosting providers, so that they may eventually benefit from the liability exemption granted by article 14 of the Directive 2000/31/ EC on electronic commerce. Likewise, it is known that this exemption from liability operates only to the extent that they are limiting their activity to a neutral service, usually through a merely technical and automatic treatment of the data provided by their users, and they comply to the requirements included in the aforementioned article 14. In particular the only activities which can exempt the provider from liability are: acting as a mere conduit, caching and hosting – but only if certain prerequisites are met, such as for the host not being aware of any illegal activity on their servers.

One of the fundamental aspects of the new article 17 of Directive (EU) 2019/790 is that one of its premises regards a partial “failure” of the situation until now existing within the EU, in the sense that the liability limitations for service providers are homogeneous in the ECD, that is, they are applicable regardless of the subject and type of responsibility. The new article 17 establishes a specific liability (and exemption) regime for a category of service providers in relation to a specific matter, the protection of copyright, which displaces the “old” regulation. In addition the specific liability regime refers exclusively to a new category, that of "online content-sharing service provider", which is defined in article 2.6) of Directive 2019/790. Specifically, this category includes any “provider of an information society service of which the main or one of the main purposes is to store and give the public access to a large amount of copyright-protected works or other protected subject matter uploaded by its users, which it organizes and promotes for profit-making purposes.”It constitutes, in principle, a subcategory among the providers to which Article 14 ECD refers. Indeed recital 62 of Directive 2019/790 indicates that the liability exemption should not apply to service providers whose main objective is to engage in activities that is harmful to or infringes copyright.

3. Controversies: article 13 vs article 17

We have seen in the past few years the rise of a great debate centered around such regulation, indeed the issue revolving around the article 17 (ex article 13) has had a huge impact from the social point of view, as stated beforehand. The debate has been taken out from the halls of the Bruxelles and reached the squares of the main European cities and, of course, the biggest public square of all: the internet. Great personalities who contributed to the growth of the internet we know nowadays did take a stand against such regulation. Not only the founder of Wikipedia Jimmy Wales expressed his concerns regarding the article 13, but also the “founder” of the internet itself Tim Berners-Lee. [1]

The proposal, which can be defined a “prototype” of the current Directive 2019/790, dates back to 2016 (COM/2016/0593 final). The article 13 had a different formulation back then: it was much shorter and had no reference whatsoever to any regime of exception, moreover the proposal considered measures that could help preventing copyright infringement “such as the use of effective content recognition technologies” to be “appropriate and proportionate”.

It’s evident why many people found upsetting the absence of an exception regime that would have excluded the liability of the provider and henceforth its obligation to take down the “unauthorized act of communication”. Such gap have been filled by paragraph 7 of article 17, which now includes “quotation, criticism, review” of user-uploaded copyright-protected works and their “use for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche” as exceptions from the delineated regime. Although such formulation might not be deemed particularly satisfying, whereas not including exhaustingly all uses of copyright-protected works which see internet users as an “active” part in the creation of new derived works.

We are living in the age of Remix Culture (as Lawrence Lessig would say) ; online users have long assumed the role of creators, not mere enjoyer of said works. Prohibiting online users from creating and diffusing works created by themselves, even if they contain references to certain copyright-protected works can - in the year 2020 in which pop culture have long assumed a role of central importance in the social development of the single person - be considered a violation of the Right of Expression (art 21 Italian Constitution, art 11 CFRUE, art 10 ECHR) .

Unlike the US, the European Law Systems aren’t familiar with concepts such as “fair use”, a parameter created by American jurisprudence that helps establishing whether the use of copyright-protected material (without the consent of the holder of such right) may be deemed lawful or unlawful.

The European Parliament, as stated before, have instead preferred to formulate a proposition inside article 17.7 which delineates in a peremptory manner “our fair use” , but it appears that the wording used isn’t completely satisfying.

“Online content-sharing service providers” , or better, their users, may need an additional liability exemption in order to fully secure the user’s right of expression. The term “pastiche” , being a word commonly used to indicate “a piece of art, music, literature, etc. that intentionally copies the style of someone else's work” , can’t really cover the wider area of user-created content (such as fanart and/or fangames /fancomics et similia) , since it refers (in the commonly used language) exclusively to the “style” of a certain work whilst leaving “uncovered” central elements of the work such as the subject.

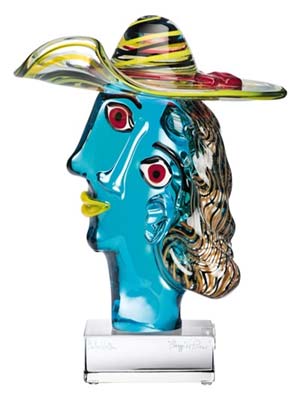

Here we have a “pastiche”: here the artist Furlan Walter intentionally “copies” the style of Pablo Picasso in order to create a Murano glass sculpture.

Instead here we can see a “fanart” , a picture created by an online user depicting several characters from the Japanese cartoon “Lupin the 3rd” which are protected by copyright; said rights of course belong to another person and not to the user who created the picture.

Regarding “content recognition technologies” it must be said that YouTube already has used for several years an automated “copyright filter” but many critics pointed that such algorithm was not fully effective. According to said critics no bot can replace human control yet; in particular there have been many cases of such algorithm taking down user-created content that did not infringe any copyright. For instance, a bot could easily take down the video of a movie review because the user who uploaded the video included some scenes from the movie he’s reviewing – although the article 17.7 expressively states that “quotation, criticism, review;” do not infringe any copyright and related rights. There have also been several cases of grave abuses of such copyright claim system by anonymous blackmailers who made use of extorting methods in order to receive sums of money from YouTube content creators . [2]

The new provision delineated in article 17.9 appears to have managed to find a somewhat balanced solution. Online content-sharing provides are now requested “without undue delay” to “put in place an effective and expeditious complaint and redress mechanism that is available to users of their services in the event of disputes over the disabling of access to, or the removal of, works or other subject matter uploaded by them” , so a user of such content-sharing providers who gets wrongfully deleted their uploaded content should now always benefit from a complaint and redress mechanism. Furthermore any decision taken “to disable access to or remove uploaded content” must now “be subject to human review” : an effort from which no provider should rightfully avoid making; the user’s fundamental right of expression shall be granted and not be subject to the errors of a bot or algorithm who cannot be expected to know how to make a distinction between a case of violation of copyright and a case of liability exemption.

To conclude, it must be also noted that now “member States” are now requested to “ensure that out-of-court redress mechanisms are available for the settlement of disputes”.

4. The 2019/790 Directive and the Italian Parliament

Nowadays the debate has arrived in the Italian parliament (to be precise in the Senate at the moment) although the main focuses are at the moment articles 5 6 14 and 22 .

It must be noted though that Confindustria during the “2020-05-12 Informal hearing with FIEG, Confindustria digitale, Confindustria cultura Italia, ANICA, APA, FAPAV, AIB" [3] did indeed take a position regarding article 17 and how the Italian legislator is trying to implement in the national legal system. During the informal hearing it was pointed out that the level of diligence requested by article 17.4 is satisfied only if “best efforts” are made in regard to the obligations stated, not “reasonable efforts”; in the Italian transposition such level of diligence were tempered by the principle of reasonableness; Confindustria made the senators notice that the European Legislator’s intention were to apply said principle only to Cultural Heritage Institutions (art 8.5 and 8.7), which have far less instrumental and economical means than corporations such as Google - means needed in order to ensure the respect of precepts stated in the EU Directive 2019/790. As a matter of fact said Law Draft is being amended, appearing now much closer to the original provision from Directive 2019/790.

Some words must be spent on the “2020-05-14 Informal hearing with FNSI, CRUI, SIAE, Wikimedia Italia, Google, Nuovo IMAIE, FIMI, MPAA, AISA, GOIPE, Creative Commons, Hermes, Movimento consumatori, ANAC Autori, Altroconsumo” [4] too, in particular regarding the intervention of Altroconsumo.

According to Altroconsumo (and as stated in the paragraphs beforehand) we are living in the age of Remix Culture where internet users have assumed an active role: the role of creators. Any legislation concerning copyright-protected works must now acknowledge said “change”: this means that every Italian (and European) citizen have a right to creation and diffusion of culture and contents, even if such contents present references to other copyright-protected works. limitation to such capability means a limitation to the right of expression

Furthermore Altroconsumo in regard to the 9th paragraph of article 17 stated that in the controversies concerning user-created contents must see as participant, by the side of the online user, a “consumer association”.

5. Article 17 according to the Polish government

Although somewhat ironical the Polish government has expressed its concerns over the fact that the 2019/790 EU directive may have negative effects on the fundamental right to the freedom of speech [5]. The Polish government declared it would not implement said directive fully, only partly , in a way that will preserve such freedoms. The Polish government, most importantly, has also decided to bring an action before the CJEU claiming the article 17 should be annulled since it contrasts with art 11 CFRUE (being in fact the fundamental rule which establishes the right to "Freedom of expression and information")

According to Poland the obligation imposed on the online content-sharing service providers regarding the application of best efforts - in order to ensure that "illicit" user-uploaded contents are made unavailable - will indeed make mandatory for said providers to automatically filter the user-uploaded content; this means that an algorithm-driven preventive control mechanism should be implemented, and since providers do not face any serious risk when limiting user rights by blocking access to "legal" content, this might create a strong incentive for over-blocking. The Polish government states that such preventive mechanisms poses a serious threat to the right of freedom of expression and information”, which would violate the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. According to Poland this is an unnecessary limitation to the freedom of expression. For once, maybe, a not-fully-democratic country might teach us Western Europeans on freedom.

6. How article 17 should be interpreted according to the European Commission and the European Council

By reading article 17.4 (b) and article 17.7 it can be noted that there is a very subtle conflict of norms between the two: the former imposing an obligation to make best efforts in order to prevent the availability of specific works and the latter stating that any measures implemented by providers must not lead to the prevention of the availability of works that do not infringe copyright.

According to the Commission and the Council [6] such conflict of norms can be solved by having the online content-sharing service providers implement a mechanism that limits automated filtering to "likely infringing" (and so probably illicit) uses of works, and that human review must instead be implemented in every other residual case. It should be noted that on said interpretation some notable civil society organizations (such as Wikimedia) stressed the fact that only imposing automated filtering to “manifestly infringing” (and so evidently illicit, not probably illicit) uses of works would correctly and fairly safeguard the legitimate uses of content uploaded to online platforms.

Anyhow this would furthermore imply a secondary conclusion: the uploaded content should remain available while it's under review and the removal must be disposed only once said review mechanism has come to a " verdict of guilty".

It can be argued though that the damage inflicted to rightholders, which can be caused by the availability (even for a short amount of time) of "illicit" works on content-sharing platforms is much greater than any harm to users caused by the temporary blocking of non-infringing upload, and on such grounds it can be said that the ex-post complaint mechanism contained in Article 17.9 provides sufficient protection for users’ rights.

7. Conclusions

The subject at hand is extremely complex and it's not easy finding compromises between users' rights - which, in an extremely large amount of cases are also content creators - and rightholders' interests.

European institutions should maybe have considered more the social relevance of "remix culture" , and maybe should have considered more the difference between "small" right-holders and "big" right-holders.

The first ones have a minor role in the development of pop culture and "remix culture" , and by being in a position of disadvantage, they might "rightfully" benefit the most from article 17. An independent artist might get their work unlawfully "stolen" and uploaded by other users pretending to be the original author, and this may cause a huge economic loss for the right-holder.

On the other hand major right-holders may benefit too much from the strict limits imposed on online content-sharing service providers (and their users) by said article: in such case the limitation imposed to a fundamental right such as the right of expression should not be justified. Indeed it should be noted that piracy exists and unfortunately is as diffused as ever, and of course said major holders of copyright are the most vulnerable to such crimes, and they surely can benefit from some kind of "upload filter" that providers may adopt.

Perhaps the ideal would have been the creation of a legal "double binary" , which would have established different normative regimes for different kind of rightholders.

As stated before copyright still remains an extremely complex field with different interests in contrast.

Member states have until 7 June 2021 to introduce laws within their own countries to implement the 2019/790 directive, but how it will be finally implemented by the single states remains uncertain: it will surely depend on how the Court of Justice of the European Union will solve the case Polish government has presented.

References

- https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-44482381

2. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-47227937

3. http://webtv.senato.it/webtv_comm_hq?video_evento=79301

4. http://webtv.senato.it/4621?video_evento=80701

5. https://www.communia-association.org/2019/08/21/finally-text-polands-legal-challenge-copyright-directive-published/

6. http://infojustice.org/archives/42643